“What is the chief end of man?”

“To glorify God and enjoy him forever.”

So began the Shorter Catechism, the blunt instrument through which I was inducted into the Presbyterian church as a teenager in early 1977. (Yes, apparently even in 1977 we were all ‘men’.)

We trust one God: the Love, Life and Truth who is the source and sustainer of all that was, is and will be.

Geoff Thompson, 2016 [1]

How does a confessional church induct people in faith? Geoff Thompson’s excellent work in writing a contemporary statement of faith reminded me of the importance of faith education having a credal dimension. Writing an affirmation of belief in fresh language, Geoff says “my conviction grows that the ‘faith of the church’, including its trinitarian content and structure, remains a fruitful source of wisdom; it warrants critical re-articulation rather than dismissal on the grounds of either its allegedly primitive worldview or its alleged captivity to Greek metaphysics.”[2]

How does a confessional church induct people in faith? Geoff Thompson’s excellent work in writing a contemporary statement of faith reminded me of the importance of faith education having a credal dimension. Writing an affirmation of belief in fresh language, Geoff says “my conviction grows that the ‘faith of the church’, including its trinitarian content and structure, remains a fruitful source of wisdom; it warrants critical re-articulation rather than dismissal on the grounds of either its allegedly primitive worldview or its alleged captivity to Greek metaphysics.”[2]

A faith-forming church is a teaching church: not rote doctrines on loop replay, but a thinking church, a seeking church, a transforming church.

In her brilliant book, “To Set One’s Heart,” Sara Little reminds us that to teach is to accept responsibility for helping others find meaning, to make sense of the world and to be changed as a result.[3] We are in the service of something greater than ourselves when we teach. Sarah sees faith-seeking-understanding as part of an educational quest for ultimate truth. This doesn’t sound particularly postmodern. Yet questions about truth and relativism, authority and freedom, certainty and doubt, are of necessity part of the seeking of wisdom, knowledge and truth.

In her brilliant book, “To Set One’s Heart,” Sara Little reminds us that to teach is to accept responsibility for helping others find meaning, to make sense of the world and to be changed as a result.[3] We are in the service of something greater than ourselves when we teach. Sarah sees faith-seeking-understanding as part of an educational quest for ultimate truth. This doesn’t sound particularly postmodern. Yet questions about truth and relativism, authority and freedom, certainty and doubt, are of necessity part of the seeking of wisdom, knowledge and truth.

For Sarah Little, believing and thinking aren’t the same thing. Belief “has affective (feeling), volitional (willing), and behavioural (acting) components, as well as cognitive (thinking).”[4] When we explore belief, we wrestle with the relationship between what we know, how we live, and what really matters to us. Sarah reminds us that credo, the root of ‘creed’, means “I set my heart.”[5]

Another meaning of “credo” is to pledge allegiance. To commit to a cause, such as “Make Poverty History,” is to do more than make a click-response to a GetUp email campaign. This kind of promise is a heart-and-mind-choice to live differently because you believe in a different future and want to live towards a transformed world. Geoff Thompson’s phrase, “We trust,” in place of “We believe ” from the Creeds takes us beyond cognition to confession, the kind of affirmation that includes our affections, desires and behaviours.

More than any other recent Protestant educator, John Westerhoff sought to reclaim catechesis as encompassing both formation or socialisation in faith and intentional education.[6] John reacted to a church that did not include the whole people of God in its worship and then sent people off to age-segregated classrooms to school them in Christian faith. He sought to remind the church that a schooling paradigm of passing on the faith is insufficient in itself. A faith-forming community is essential as both context and condition for discipleship. John did not dismiss the need for intentional education in Christian faith. “Intentionality” is my buzz-word when it comes to both formation and education. Stay tuned and you’ll hear it a lot.

More than any other recent Protestant educator, John Westerhoff sought to reclaim catechesis as encompassing both formation or socialisation in faith and intentional education.[6] John reacted to a church that did not include the whole people of God in its worship and then sent people off to age-segregated classrooms to school them in Christian faith. He sought to remind the church that a schooling paradigm of passing on the faith is insufficient in itself. A faith-forming community is essential as both context and condition for discipleship. John did not dismiss the need for intentional education in Christian faith. “Intentionality” is my buzz-word when it comes to both formation and education. Stay tuned and you’ll hear it a lot.

Teaching the faith takes place in the context of a worshipping, witnessing community of faith. There is no way to learn or understand Christian discipleship other than to be with people who seek to live it. I love Geoff Thompson’s extensive use of verbs to describe the person and mission of Jesus Christ and the activity of the Holy Spirit – sent, serve, proclaimed, healed, befriended, forgave, confronted, inspired. This not only draws attention to the dynamic presence and purpose of God, but clearly echoes the lives of those who confess their faith in Christ by the power of the Spirit. We see and hear who we might be called to be as the creed is voiced boldly and recklessly. We are sent. We proclaim. We make friends. We confront. We forgive. We inspire. We serve.

I wonder whether the test of a good confession of faith is whether it can be shouted in an African church where people respond loudly and with joy! Amen! Yes! Hallelujah! Thank you Jesus! African-American churches speak their tradition as testimony, celebration and confession. It is pentecostal! The Spirit is alive and among us now! This is the power of liturgy, whether scripted or extemporaneous – to grab us, hold us, change us.

In her recent book, Christian Education and the Emerging Church, Wendi Sargeant describes this as the connection between tradition (passing on or transmission) and traditium (knowledge, rituals and practices). [7] What we know, how we know and how we live are inter-connected. There is an interplay between how we make sense of our confessions and how we live as a flawed community of disciples. The fact that consumerism is rampant is Western culture is proof of this. As a church we need to pay attention to the ritualising of meaning through the practices of everyday life, not just within worship. If growing disciples is about becoming people who confess the faith, then we need to pay more attention to how it happens outside corporate worship, outside the church building, in what John Roberto calls non-gathered settings. Cultural theorists see the popular culture of everyday life as more than leisure; it is where we make meaning through stories, relationships and ritual practices. I highly commend Steve Taylor’s “Out of Bounds Church” as a way to explore this.

In her recent book, Christian Education and the Emerging Church, Wendi Sargeant describes this as the connection between tradition (passing on or transmission) and traditium (knowledge, rituals and practices). [7] What we know, how we know and how we live are inter-connected. There is an interplay between how we make sense of our confessions and how we live as a flawed community of disciples. The fact that consumerism is rampant is Western culture is proof of this. As a church we need to pay attention to the ritualising of meaning through the practices of everyday life, not just within worship. If growing disciples is about becoming people who confess the faith, then we need to pay more attention to how it happens outside corporate worship, outside the church building, in what John Roberto calls non-gathered settings. Cultural theorists see the popular culture of everyday life as more than leisure; it is where we make meaning through stories, relationships and ritual practices. I highly commend Steve Taylor’s “Out of Bounds Church” as a way to explore this.

The contemporising of creeds is more than passing on tradition. It involves making sense of faith in the light of current knowledge – religious, scientific and philosophic. Val Webb consistently argues for the importance of engaging theological questions in the broader realm. Val says “… doubt is not…the antonym of either faith or belief. The opposite of faith is to be without the experience of faith. The opposite of belief is unbelief. Perhaps the best way to talk of doubt in relation to faith and belief is to see doubt as the awareness of a discrepancy between faith and belief… Doubts occur when the belief system does not line up with our experience.” [8] In her writings, Val highlights both the narrowing of theological conversation through confessional certainty and the exclusion of ‘lay people’ from theological enquiry and conversation. The church has taught its members to be quiet in the face of its theological expertise, silencing their own confessions of faith, private and public.

The contemporising of creeds is more than passing on tradition. It involves making sense of faith in the light of current knowledge – religious, scientific and philosophic. Val Webb consistently argues for the importance of engaging theological questions in the broader realm. Val says “… doubt is not…the antonym of either faith or belief. The opposite of faith is to be without the experience of faith. The opposite of belief is unbelief. Perhaps the best way to talk of doubt in relation to faith and belief is to see doubt as the awareness of a discrepancy between faith and belief… Doubts occur when the belief system does not line up with our experience.” [8] In her writings, Val highlights both the narrowing of theological conversation through confessional certainty and the exclusion of ‘lay people’ from theological enquiry and conversation. The church has taught its members to be quiet in the face of its theological expertise, silencing their own confessions of faith, private and public.

Any lack of conformity between confessions of faith and how we live is not just a lack of application, but a dissonance of knowledge. This is not just about thinking (theory or theology) versus acting (practice). We know through ‘experience’ and we know through ‘belief’. In examining what apprentices know and how they know it, Lave and Wenger said that both the classroom and the workshop have their own truths, their explicit and implicit theories and practices. [9] We are not and never should be a church of theologian=theory vs ‘lay person’=practice.’ Faithfulness to God involves not only revising our actions in the light of Christian teaching but reforming doctrine in the light of our experience of God in God’s world.

Any lack of conformity between confessions of faith and how we live is not just a lack of application, but a dissonance of knowledge. This is not just about thinking (theory or theology) versus acting (practice). We know through ‘experience’ and we know through ‘belief’. In examining what apprentices know and how they know it, Lave and Wenger said that both the classroom and the workshop have their own truths, their explicit and implicit theories and practices. [9] We are not and never should be a church of theologian=theory vs ‘lay person’=practice.’ Faithfulness to God involves not only revising our actions in the light of Christian teaching but reforming doctrine in the light of our experience of God in God’s world.

Val Webb’s most recent book invites us to see engagement with the tradition of the church as part of the work of the whole people of God. [10] She suggests that to be an inquiring church requires “compassionate theological hospitality,” allowing us to be a community of respectful mutual learning. [11] I heartily agree that a church’s lack of capacity to engage in theological enquiry is often related to its climate as a learning community. The tendency to systematise belief, synchronise faith or disparage doubt too readily stifles honest enquiry and people’s sense of belonging to a community who are still working out their faith.

In his comprehensive study of Confirmation, Richard Osmer said that many educational and ritual practices that should be part of the regular faith growth of Christians are isolated and condensed into a very small period of time. [12] Church attenders are, by design or default, denied opportunities to dig into the substance of the faith, let alone have the space to frame their own confessions connecting belief and faith (to use Webb’s terms). Interestingly, Osmer sees such practices as connecting doctrinal catechism and biblical catechesis. For me, Geoff Thompson’s theological narration of Scripture both expresses and invites such connection. We could all read Geoff’s affirmation, but what if we were playing with making our own individually or together?

In his comprehensive study of Confirmation, Richard Osmer said that many educational and ritual practices that should be part of the regular faith growth of Christians are isolated and condensed into a very small period of time. [12] Church attenders are, by design or default, denied opportunities to dig into the substance of the faith, let alone have the space to frame their own confessions connecting belief and faith (to use Webb’s terms). Interestingly, Osmer sees such practices as connecting doctrinal catechism and biblical catechesis. For me, Geoff Thompson’s theological narration of Scripture both expresses and invites such connection. We could all read Geoff’s affirmation, but what if we were playing with making our own individually or together?

When I studied the confirmation practices of a number of mainline churches in the late 1990’s, I was impressed by the approach to confirmation taken by St Mary’s Press, a Catholic publisher in Minnesota. Tom Zanzig explained to me that their approach with younger teenagers was to help the recognise their faith an ongoing journey of maturation. Confirmation was not a graduation. After exploring the faith of the church, young people were invited to frame their own ‘creeds’ or faith statements as a response. The rite of confirmation then became a shared promise by the young person and the congregation to continue to explore and learn about the faith together, since both were on a journey of growing in faith and understanding. Confirmation and its confessing of the faith was not seen simply as a ritual act but as a way of life of a people who have not yet arrived at perfect understanding, let alone perfect obedience!

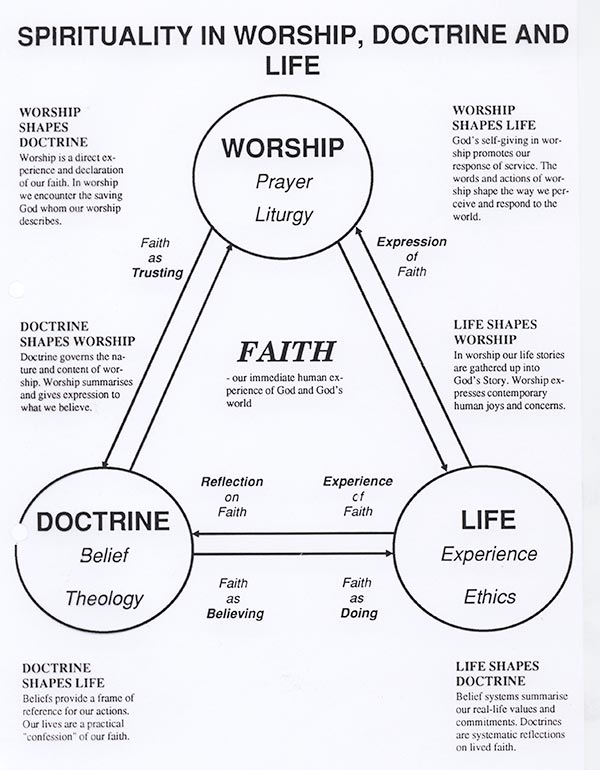

In 1988, fresh from Duke Divinity School, I sought to synthesise Sara Little’s work with that of my theology teacher Geoffrey Wainwright’s Doxology and a bit of my own thinking using the following diagram (used in some teaching at the time). [13] In my mind it has a great degree of resonance with Wendi Sargeant’s recent work. While some of it probably requires further or better explanation, and some of the categorisations don’t hold particularly well, it nevertheless expresses something of what I’m trying to say here.

In 1988, fresh from Duke Divinity School, I sought to synthesise Sara Little’s work with that of my theology teacher Geoffrey Wainwright’s Doxology and a bit of my own thinking using the following diagram (used in some teaching at the time). [13] In my mind it has a great degree of resonance with Wendi Sargeant’s recent work. While some of it probably requires further or better explanation, and some of the categorisations don’t hold particularly well, it nevertheless expresses something of what I’m trying to say here.

Download Worship_Doctrine_Life 5mb PDF.

What if the confessing of the faith

-in word and deed

– in credal statements

– in stories through the ages

– in poetry and songs

– in images and movement

– with its experiential challenges

– with its interpretive questions

was included more intentionally within the educational ministry of the church?

What if we were making new creeds through prose, music, dance, art, poetry and craft as ways of learning about and stretching our faith?

What if the kinds of connections described by the six arrows were part of the educational dynamic of what it means to be a confessing church? It is interesting in our postmodern (or late modern world) to see a strengthening interest in churches and religions articulating matters of belief. I commend Wendi Sargeant’s book as a rich way of thinking deeply about these exact issues.

This turned from a post into a mini-essay. Thanks to Geoff Thompson for provoking this reflection, and he is in no way implicated in my views expressed here!

Craig Mitchell

February 2016

References

- http://xenizonta.blogspot.com/2016/01/a-confession-of-churchs-faith.html

- Ibid.

- Little, Sara, To Set One’s Heart: Belief and Teaching in the Church, Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1983.

- Ibid, p7.

- Ibid.

- Westerhoff, John H III and Edwards, O.C. Jr, A Faithful Church: Issues in the History of Catechesis, Wilton CT: Morehouse-Barlow, 1981.

- Sargeant, Wendi, Christian Education and the Emerging Church, Eugene: Pickwick, 2015.

- Webb, Val, In Defence of Doubt, Northcote: Morning Star, 2012.

- Lave, Jean and Wenger Etienne, Situated Learning, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Webb, Val, Testing Tradition and Liberating Theology, Northcote: Morning Star, 2015.

- Ibid, p238.

- Osmer, Richard, Confirmation, Louisville: Geneva Press, 1996.

- Wainwright, Geoffrey, Doxology, New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Leave a Reply