Our text yesterday was John 15 and the emphasis was on being disciples. We talked about paying attention.

I touched on three themes

- To abide in Christ is to pay attention to the narrative of Jesus in the past – that of course is primarily in the Gospels – and also to what Christ says to us today through the Holy Spirit

- We abide in Christ so that we might know the love of God and know what God is doing

- Only when we abide in Christ’s love together can we united, obedient and bear fruit

Today I want to explore a second text that arises from my research into forming and educating lifelong disciples, and in a sense to focus on what disciples do. Again I want to link it with one of the stories from my research about growing disciples.

But first….

In this time when we seem to reinventing church, what is essential and what is secondary?

Our text is a very familiar one from Acts chapter 2. Before we read and discuss the text, I’m going to invite you in a moment to take yourself back in your imagination to the time of Pentecost. The invitation is to place yourself within the story, not just as en exercise in creative thinking, but as an act of prayer – to listen for the Spirit today.

Download Guided_meditation_Acts_2 (PDF)

What has been your richest experience of Christian community?

My first answer would be when on four occasions I was a member of a Scripture Union Beach Mission at Noosa in the late 70’s. Yes, Noosa. “Lord, here am I! Send me! About 40 of us would spend a week in Bible study, prayer and sharing the gospel with unsuspecting holiday-makers. And playing Jesus songs.

My first answer would be when on four occasions I was a member of a Scripture Union Beach Mission at Noosa in the late 70’s. Yes, Noosa. “Lord, here am I! Send me! About 40 of us would spend a week in Bible study, prayer and sharing the gospel with unsuspecting holiday-makers. And playing Jesus songs.

But I had a much more profound experience a decade later when we were living in the US. Through the university, we applied to stay with a host family over Christmas, and ended up in Lebanon, Pennsylvania with a Mennonite family.

Living with Mennonites

If you don’t know of Mennonites, they come from the Anabaptist tradition. The Amish people broke away from the Mennonites because they thought they were too liberal. We spent Christmas with Daniel and Joyce Miller and their two daughters – and the Hoover clan, Joyce’s family, who were dairy farmers – and their faith community. And we were changed.

What we experienced wasn’t a temporary youth camp – but the life of a people. Dan was a carpenter who took on former prisoners as apprentices. He wanted to help them get a fresh start and he was and is an evangelist. When Dan and Joyce applied to host international students, they were hoping to get a couple of atheists or maybe Buddhists, and initially they were SO disappointed to receive a couple from Duke Divinity School.

This changed my life. As a suburban Australian Presbyterian, for the first time I encountered a kind of Christian ‘tribe’ who saw themselves as counter-cultural, who lived simple yet incredibly generous lives, who met constantly for prayer and Bible study (after all there was no TV in their homes), and who were passionate about sharing the story of Jesus and serving the poor. And like the early Christians, they refuse to go to war for the Empire.

This was quite foreign to my experience of church in Australia. I had a glimpse of a kind of intentional Christian community that was possible. Even the very short time that we spent living with the Millers and their extended family had a deep and lasting effect on us. We forged a deep friendship and went back to visit with them again and again.

How deep was the impact? Well, I was studying with Stanley Hauerwas and had been reading John Howard Yoder’s “Politics of Jesus”. When I met Mennonites, I realised that a life of discipleship shaped around non-violence was real for some Christians. I became committed to a way of living as a disciple, committed to non-violence, that was grounded in the example and teaching of Jesus.

If that sounds like a sound-bite of a testimony of transformation, for me, that is exactly what it is. And you will have had times like that in your own life of discipleship. I also count it among a few critical turning points where I experienced faith outside my own familiar culture.

Today I want to focus on how we learn to do what disciples do, on the habits or practices of discipleship – what they are and how we learn them – and what it means to call people to a be disciples on a Way that is counter-cultural, and bears sole allegiance to Jesus Christ.

Acts 2:42-47

Changed Lives

This image of the early church seems idyllic, doesn’t it? A joyful, close-knit, intimate community who share everything and look after everyone. One mind, one heart, one bank account. (Sounds like a marriage.)

Although the picture might seem to be painted in bold, exaggerated terms, it IS a story about the Spirit breaking into people’s lives to do something fresh – to bring to fruition all that Jesus promised. It IS part of the cosmic drama of salvation that God is unfolding through history – the new age of the Spirit.

The disciples’ pattern of life is changed by the Pentecost experience. All that they have learned from Jesus seems suddenly to take shape – a community who continually and even recklessly love God and love their neighbour.

The early church is birthed from the Jewish faith, among faithful Jews along with Gentiles who have been part of the Jewish community. It isn’t born in a vacuum, but within the way of life of the Jewish people – in the Temple and in their homes, and in the context of their daily lives – their regular Temple worship and prayer, their habits of eating together and studying the Scriptures, their religious virtues of hospitality and generosity.

And yet the Epistles and the book of Acts tell of a transformation in people’s lives as the gospel spreads from being an subset of Jewish faith to the Gentiles right across the Middle East. So what happens?

For a few reasons, neither the Temple in Jerusalem, nor the synagogues in neighbouring cities, can contain this growing movement. Temple life has its own order and hierarchy. The followers of Jesus have their own story to tell, and a faith to figure out. They’re constantly asking “What is different for us because of what Jesus taught and who he was?”

Meeting in Homes

So they meet in the homes of members of the community. And this makes sense, because that’s where people gather when you’re not working or at the place of worship.

Imagine a courtyard with several dwellings facing the courtyard – some of the dwellings are only one room, say 5 metres square. Some have an extra room build on top or another room out the back. The family live and sleep in the single room. The second room would be housing grandparents, or uncles and aunts and cousins, or visitors on business. A larger household might have servants, or if a Gentile household, slaves. How many people live there? Well it depends on the household and the size of the place. 10, 20, 30.

Every front door opens to the courtyard. The cooking is done out the front of the house in the courtyard. Every household in this courtyard knows everyone else’s business.

Some of the many pilgrim converts following the Day of Pentecost stayed in Jerusalem, and the Christians of the city offer them hospitality. Their houses are suddenly overflowing with guests.

Oikos and Ekklesia

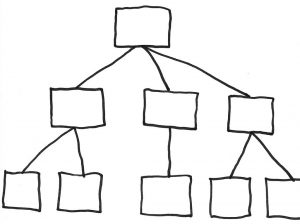

And these households, these ekklesia or assemblies, become the basic unit or cell of the church.

The new Testament speaks of these gatherings as ekklesia but also as oikos, or households. Oikos is the Greek word from which we derive the words economy and ecumenical. So it’s not simply talking about a building, but the basic social and economic unit of society.

The household was the hub of everyday life. While biblical scholars differ as to whether the early Christian movement was predominantly a middle class movement or much broader, it is evident that there were patrons wealthy enough to host an assembly. So when Paul and others travel to other cities to spread the good news, the local synagogue can be a starting point for meeting people and sharing the faith, but at some point, local believers host an assembly.

The oikos hosts the ekklesia – church is going to meet in my house. Every day. And stay over. And that’s when gospel and culture get really interesting.

Up Close and Personal

I have a confession to make. The way I behave at church and the way I behave at home aren’t 100% the same. On rare occasions, I display attitudes and behaviours at home that might cause people at church to raise their eyebrows a little. I know that’s hard to believe and that you can’t relate to it at all.

But I’ve had the experience, only once or twice, of course, where we’re having guests over to our place for dinner, and Craig, the kitchen Nazi, is madly trying to get everything organised, and quite flustered, and uncharacteristically crabby with the staff. The doorbell rings. The guests have arrived, but the meal isn’t quite ready. We welcome them warmly, but because I’m SO FOCUSED on creating the perfect dish for our guests, they then hear me speak to the staff, sorry, family members, in a manner that they’ve NEVER heard me use in church. “I NEED THAT ON THE TABLE NOW!” You have no idea what I’m talking about, but when that happens, there’s a kind of mutual pause and an unspoken moment of recognition – and then suddenly it becomes a very polite evening, even though the meal isn’t quite up to MY expectations.

But I’ve had the experience, only once or twice, of course, where we’re having guests over to our place for dinner, and Craig, the kitchen Nazi, is madly trying to get everything organised, and quite flustered, and uncharacteristically crabby with the staff. The doorbell rings. The guests have arrived, but the meal isn’t quite ready. We welcome them warmly, but because I’m SO FOCUSED on creating the perfect dish for our guests, they then hear me speak to the staff, sorry, family members, in a manner that they’ve NEVER heard me use in church. “I NEED THAT ON THE TABLE NOW!” You have no idea what I’m talking about, but when that happens, there’s a kind of mutual pause and an unspoken moment of recognition – and then suddenly it becomes a very polite evening, even though the meal isn’t quite up to MY expectations.

When your faith community only see one another at worship for an hour and a half, you might be an assembly but you’re maybe not a household. When you live closely with strangers, particularly people of different values or faith or behaviour, you change.

Household Structure

The oikos has a structure – a head of the house (sometimes male, but also women) – husbands and wives, deference to grandparents, parents and children, guests and business partners, servants and slaves. The household has rules, some religious and some cultural, that provide a pattern for life.

The oikos has a structure – a head of the house (sometimes male, but also women) – husbands and wives, deference to grandparents, parents and children, guests and business partners, servants and slaves. The household has rules, some religious and some cultural, that provide a pattern for life.

Suddenly, into this structured, ordered household, there are newcomers to the faith – maybe family and friends, out of town visitors, strangers who have been helped or healed. And the household, and then the wider community, gets shaken up – the household order, the family order, the religious order, the cultural order

Roman society has guilds and clubs – some are based on vocation and some are more social – but they are free associations of people from more or less the same class. The Temple and synagogue have their own kind of community life, and these are of course centred on the particularities of Jewish faith and Jewish culture. There are also schools of philosophy, but these have a certain learning focus, and are also limited by class.

In Galatians 3, Paul says:

As many of you as were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.

This radical equalisation of people in Christ challenges the Jewish faith, challenges household life, and challenges Roman life.

Imagine an orderly Jewish household where suddenly there are 24/7 live-in guests and a daily assembly of believers, where there is no longer male nor female, slave nor free, Jew nor Greek! How is that supposed to work?

Imagine an orderly Jewish household where suddenly there are 24/7 live-in guests and a daily assembly of believers, where there is no longer male nor female, slave nor free, Jew nor Greek! How is that supposed to work?

What will the neighbours think? “Guess who’s coming to dinner?” “Gentiles? Did you say Gentiles?” “They put WHAT on the BBQ??”

“Neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female”. Social roles and rules are thrown into chaos by the Gospel. Why is there so much in the Epistles about how to behave if you follow the way of Jesus?

Even Paul himself is trying to work out how people live out of this equality – whether or not women should be allowed to speak publicly or dress differently; whether or not women and slaves are free to reject their place in the social hierarchy. How should husbands and wives treat each other? How should slaves react to their masters?

These assemblies are characterised by a radical inclusivity that will welcome all, but as a household, their ways of living, relating, and sharing daily are provoked and transformed in ways that are counter-cultural to both Jews and Gentiles.

What is clean and unclean? Do Gentiles need to becomes Jews? What about class distinctions in Roman society – owners, slaves, freed slaves?

The Way of Jesus says all are One in Christ Jesus. These Christians don’t just tolerate one another, they speak of themselves as in highly relational terms as one body, one household, one family.

If you read Acts 2 through this kind of lens, the early church is characterised by an egalitarianism and an inclusiveness that require their daily habits to change. Jews break bread with Gentiles. Slaves are worthy of respect. The wealthy share with the needy.

Some commentators, of course, see this daring lifestyle as evidence that the early believers expected Jesus to return soon. Sell the farm! Free your slaves! Some describe the quality of community life in Acts more in spiritual than in practical terms. For some, however, this is describing both a spiritual and practical pattern of life, of mutuality, of generosity, of inclusivity that is, in fact, the Way of Jesus.

The koinonia of the early church is distinctive because of its inclusiveness and equality. This is a community of mutual acceptance and respect, though it comes at a price for them where the gospel challenges their culture and beliefs.

The community life is also distinctive because it calls people to a disciplined Way.

Christians offer their ultimate allegiance not to the Empire but to Christ. They are counter-cultural, both in relation to Judaism and to Roman culture, because of their radical obedience.

This is a free association of people who, in a sense, give up their freedom to be followers of Jesus. Freedom and obedience.

So if underlying Acts 2 is new identity in Christ, it is an identity both given by God, and learned by incorporation into a community of daily worship, learning from the apostles, shared eating and living, and sharing possessions.

How do you learn to be a disciple? By living it.

In my view there are four distinctives that make this discipling vibrant and transformative:

- These are intimate, day-to-day, living in each other’s pockets fellowships – extended, intergenerational, multi-cultural, multi-vocational households. Anglo Westerners don’t get this, but people from African cultures, Asian cultures and Latin American cultures, and the First Peoples of this place – that’s how they live.

- They are actively working out what the faith means.

They have the Hebrew Scriptures and the stories and teaching of the apostles, and that’s it. Faith isn’t locked inside a box – what we believe and how we live is actually a work-in-progress – that’s what the Epistles are all about. They are discussing faith and ethics all the time. - They’re living in a courtyard with their neighbours.

Their faith may be distinctive but it’s not cloistered. Not at all. There is a transparency about their Christian communal life (which is also their home life). So the habits of faith, the ethics of faith, the signs and wonders of faith aren’t bound up inside the four walls of the synagogue. They are visible to extended family, neighbours and co-workers. - This is the work of the Holy Spirit bursting out in all kinds of amazing ways.

Mark Powell says that the only thing missing from the book of Acts is dinosaurs! You could add them in and they wouldn’t seem out of place. They don’t have a church growth manual. They weren’t playing “Survival of the Synagogue.” The believers were filled with joy! Luke’s picture of the habits of discipleship is one of a Way of life propelled by the Spirit in worship, the Spirit in faith-sharing, and the Spirit in compassion. Sounds like “worship, witness and service” to me.

These are the two poles which the gospel somehow holds together: radical Welcome and a radical Way to follow.

In my congregational research, I visited the Queenscliff and Point Lonsdale congregations on the Bellarine Peninsula on the western side of Port Phillip Bay, near Geelong, and interviewed the ministers there, Charles Gallacher and Kerrie Lingham. They are a married couple sharing a full-time placement. At that stage they had been there for 14 years. They told me that the big change happened after 7 years, when they went from having a morning service at each of the two congregations to one morning service at each location for 3 months at a time. That meant they could start a Wednesday evening community meal followed by a contemplative service which has become the buzzing hub of their life together. Their community is marked by inclusion (no ‘us’ and ‘them’), a focus on spiritual practices, and a strong engagement with issues of social justice.

[Following is the video that I didn’t show because of lack of time.]

Charles Gallacher and Kerrie Lingham Part 2 from Craig Mitchell on Vimeo.

[There is another excerpt of my video interview here.]

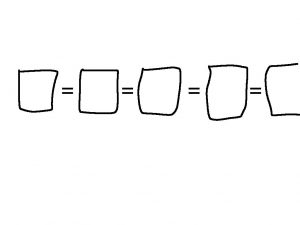

A number of authors have identified the ministries or practices of the early church.

In her book Fashion Me a People, Maria Harris names the following

Leiturgia – worship and prayer

Koinonia – community, caring

Didache – teaching and learning

Diakonia – service and justice

Kerygma – proclamation, witness

US Methodist Robert Schnase talks about Five Practices of Fruitful Congregations:

US Methodist Robert Schnase talks about Five Practices of Fruitful Congregations:

- Radical Hospitality

- Passionate Worship

- Intentional Faith Developmenet

- Risk-taking Mission and Service

- Extravagant Generosity

Schase says that the adjective in front of each practice describes its purposeful and radical nature, that which makes it distinctive and transformative.

Handout

- Christian practices are things we do together over time in response to and in the light of God’s active presence for the life of the world.

- Practices address fundamental human needs and conditions through concrete human acts. However, they are not treasured only for their outcomes… [People] understand what they do as part of the practice of God. They are doing it not just because it works (although they hope it does), but because it is good.

- Practices are done together and over time… a practice has a certain internal feel and momentum.

- Practices possess standards of excellence.

- When we see some of our ordinary activities as Christian practices, we come to perceive how our daily lives are all tangled up with the things God is doing in the world.

- Practices are all interrelated.

Dorothy Bass, Practicing Our Faith, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997

After reading quite a few books about practices, I’ve compiled my own list for working with congregations:

After reading quite a few books about practices, I’ve compiled my own list for working with congregations:

- Transformative Worship

- Intentional Learning

- Radical Hospitality

- Risk-Taking Mission

- Authentic Witness

- Persistent Prayer

- Just Living

- Generous Giving

Download Practices_Cards (PDF)

So the habits or practices of the early church exemplify the mission and message of Jesus.

Just at the disciples learned from Jesus by accompanying him on the road, we learn about following Jesus in the company of those who are also on the journey with him – some older and more mature, and some younger with questions and dreams that would never occur to us.

The early church is marked by the intimacy of its households of faith and the transparency of their alternative way of life.

In The Gospel in a Pluralist Society, Lesslie Newbiggin says:

In The Gospel in a Pluralist Society, Lesslie Newbiggin says:

If the gospel is to be understood,

if it is to be received as something

which communicates the truth

about the real human situation,

if it is as we say ‘to make sense’,

it has to be communicated

in the language of those

to whom it is addressed

and it has to be clothed in symbols

which are meaningful to them.

And since the gospel does not come

as a disembodied message,

but as the message of a community

which claims to live by it and which

invites others to adhere to it,

the community’s life must be so ordered

that ‘it makes sense’ to those

who are so invited.

Those to whom it is addressed

must be able to say ‘Yes I see’.

I closed with a prayer from Tess Ward’s The Celtic Wheel of Year. (adapted)

Loving God,

O Constant One

Make us more faithful

as we walk this day with you

Wash our feet and show us how to serve

Place bread in our hands

for we need food for the journey

Share your cup of liberation

that we may share forgiveness

Keep us open to truthfulness

and give us courage to speak it

but should we fail

and betray another or ourselves,

show us a way back

May the mercy we receive

make us more merciful

the understanding we are shown,

help us understand

Keep our eyes awake

to the injustice that happens

right beside us

Remember us through our day,

even when we do not remember you.

Constant One,

keep faith with us

as we seek to serve you this day.

Amen.

loved this- thank you so much